Code

import pandas as pd

fruits = {

"apples": [3, 2, 0, 1],

"oranges": [0, 3, 7, 2]

}

df_fruits = pd.DataFrame(fruits)

df_fruits| apples | oranges | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 0 | 7 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 |

pandasThe pandas library (https://pandas.pydata.org) is one of the most used tool at the disposal of people working with data in python today.

DataFrame object (a table of data) with a huge set of functionalitiesThrough pandas, you get acquainted with your data by analyzing it

you get acquainted with your data by cleaning and transforming it

matplotlib, seaborn, plotly or others)pandas is a central component of the python stack for data science

Pandas is built on top of NumPyDataFrame is often fed to plotting functions or machine learning algorithms (such as scikit-learn)jupyter, leading to a nice interactive environment for data exploration and modelingThe two primary components of Pandas are the Series and DataFrame.

A Series is essentially a column

A DataFrame is a multi-dimensional table made up of a collection of Series with equal length

DataFrame from scratchimport pandas as pd

fruits = {

"apples": [3, 2, 0, 1],

"oranges": [0, 3, 7, 2]

}

df_fruits = pd.DataFrame(fruits)

df_fruits| apples | oranges | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 0 | 7 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 |

type(df_fruits)pandas.core.frame.DataFramedf_fruits["apples"]0 3

1 2

2 0

3 1

Name: apples, dtype: int64type(df_fruits["apples"])pandas.core.series.SeriesDataFrame uses a contiguous indexdf_fruits = pd.DataFrame(fruits, index=["Daniel", "Sean", "Pierce", "Roger"])

df_fruits| apples | oranges | |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3 | 0 |

| Sean | 2 | 3 |

| Pierce | 0 | 7 |

| Roger | 1 | 2 |

.loc versus .iloc.loc locates by name.iloc locates by numerical indexdf_fruits| apples | oranges | |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3 | 0 |

| Sean | 2 | 3 |

| Pierce | 0 | 7 |

| Roger | 1 | 2 |

We can pick rows

# What's in Sean's basket ?

df_fruits.loc['Sean']apples 2

oranges 3

Name: Sean, dtype: int64Note that this returns a Series

We can pick slices of rows and columns

# Who has oranges ?

df_fruits.loc[:, 'oranges']Daniel 0

Sean 3

Pierce 7

Roger 2

Name: oranges, dtype: int64# How many apples in Pierce's basket ?

df_fruits.loc['Pierce', 'apples']np.int64(0)Note that the type of the result depends on the indexing information.

df_fruits| apples | oranges | |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3 | 0 |

| Sean | 2 | 3 |

| Pierce | 0 | 7 |

| Roger | 1 | 2 |

We may also pick information through positions using iloc.

df_fruits.iloc[2, 1]np.int64(7)Note that the DataFrame has two index:

df_fruits.index

df_fruits.columnsIndex(['apples', 'oranges'], dtype='object')DataFrameA DataFrame has many attributes

df_fruits.columnsIndex(['apples', 'oranges'], dtype='object')df_fruits.indexIndex(['Daniel', 'Sean', 'Pierce', 'Roger'], dtype='object')df_fruits.dtypesapples int64

oranges int64

dtype: objectA DataFrame has many methods

Method info() provides information on the table schema, name and type columns, whether the cells can contain missing values.

df_fruits.info()<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 4 entries, Daniel to Roger

Data columns (total 2 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 apples 4 non-null int64

1 oranges 4 non-null int64

dtypes: int64(2)

memory usage: 268.0+ bytesMethod describe() provides with statistical summaries for columns

df_fruits.describe()| apples | oranges | |

|---|---|---|

| count | 4.000000 | 4.00000 |

| mean | 1.500000 | 3.00000 |

| std | 1.290994 | 2.94392 |

| min | 0.000000 | 0.00000 |

| 25% | 0.750000 | 1.50000 |

| 50% | 1.500000 | 2.50000 |

| 75% | 2.250000 | 4.00000 |

| max | 3.000000 | 7.00000 |

What if we don’t know how many apples are in Sean’s basket ?

::: {#cell-Nulling some cells .cell execution_count=18}

df_fruits.loc['Sean', 'apples'] = None

df_fruits| apples | oranges | |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3.0 | 0 |

| Sean | NaN | 3 |

| Pierce | 0.0 | 7 |

| Roger | 1.0 | 2 |

:::

None is a Python keyword. NaN belongs to Pandas.

df_fruits.describe()| apples | oranges | |

|---|---|---|

| count | 3.000000 | 4.00000 |

| mean | 1.333333 | 3.00000 |

| std | 1.527525 | 2.94392 |

| min | 0.000000 | 0.00000 |

| 25% | 0.500000 | 1.50000 |

| 50% | 1.000000 | 2.50000 |

| 75% | 2.000000 | 4.00000 |

| max | 3.000000 | 7.00000 |

Note that count is 3 for apples now, since we have 1 missing value among the 4

To review the members of objects of class pandas.DataFrame, dir() and module inspect are convenient.

[x for x in dir(df_fruits) if not x.startswith('_') and not callable(x)]import inspect

# Get a list of methods

membres = inspect.getmembers(df_fruits)

method_names = [m[0] for m in membres

if callable(m[1]) and not m[0].startswith('_')]

print(method_names)['abs', 'add', 'add_prefix', 'add_suffix', 'agg', 'aggregate', 'align', 'all', 'any', 'apply', 'applymap', 'asfreq', 'asof', 'assign', 'astype', 'at_time', 'backfill', 'between_time', 'bfill', 'bool', 'boxplot', 'clip', 'combine', 'combine_first', 'compare', 'convert_dtypes', 'copy', 'corr', 'corrwith', 'count', 'cov', 'cummax', 'cummin', 'cumprod', 'cumsum', 'describe', 'diff', 'div', 'divide', 'dot', 'drop', 'drop_duplicates', 'droplevel', 'dropna', 'duplicated', 'eq', 'equals', 'eval', 'ewm', 'expanding', 'explode', 'ffill', 'fillna', 'filter', 'first', 'first_valid_index', 'floordiv', 'from_dict', 'from_records', 'ge', 'get', 'groupby', 'gt', 'head', 'hist', 'idxmax', 'idxmin', 'iloc', 'infer_objects', 'info', 'insert', 'interpolate', 'isetitem', 'isin', 'isna', 'isnull', 'items', 'iterrows', 'itertuples', 'join', 'keys', 'kurt', 'kurtosis', 'last', 'last_valid_index', 'le', 'loc', 'lt', 'map', 'mask', 'max', 'mean', 'median', 'melt', 'memory_usage', 'merge', 'min', 'mod', 'mode', 'mul', 'multiply', 'ne', 'nlargest', 'notna', 'notnull', 'nsmallest', 'nunique', 'pad', 'pct_change', 'pipe', 'pivot', 'pivot_table', 'plot', 'pop', 'pow', 'prod', 'product', 'quantile', 'query', 'radd', 'rank', 'rdiv', 'reindex', 'reindex_like', 'rename', 'rename_axis', 'reorder_levels', 'replace', 'resample', 'reset_index', 'rfloordiv', 'rmod', 'rmul', 'rolling', 'round', 'rpow', 'rsub', 'rtruediv', 'sample', 'select_dtypes', 'sem', 'set_axis', 'set_flags', 'set_index', 'shift', 'skew', 'sort_index', 'sort_values', 'squeeze', 'stack', 'std', 'sub', 'subtract', 'sum', 'swapaxes', 'swaplevel', 'tail', 'take', 'to_clipboard', 'to_csv', 'to_dict', 'to_excel', 'to_feather', 'to_gbq', 'to_hdf', 'to_html', 'to_json', 'to_latex', 'to_markdown', 'to_numpy', 'to_orc', 'to_parquet', 'to_period', 'to_pickle', 'to_records', 'to_sql', 'to_stata', 'to_string', 'to_timestamp', 'to_xarray', 'to_xml', 'transform', 'transpose', 'truediv', 'truncate', 'tz_convert', 'tz_localize', 'unstack', 'update', 'value_counts', 'var', 'where', 'xs']DataFrames have more than \(400\) members. Among them, almost \(200\) are what we call methods. See Dataframe documentation

Among non-callable members, we find genuine data attributes and properties.

others = [x for x in membres

if not callable(x[1])]

[x[0] for x in others if not x[0].startswith('_')]['T',

'apples',

'at',

'attrs',

'axes',

'columns',

'dtypes',

'empty',

'flags',

'iat',

'index',

'ndim',

'oranges',

'shape',

'size',

'style',

'values']Ooooops, we forgot about the bananas !

df_fruits["bananas"] = [0, 2, 1, 6]

df_fruits| apples | oranges | bananas | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sean | NaN | 3 | 2 |

| Pierce | 0.0 | 7 | 1 |

| Roger | 1.0 | 2 | 6 |

This amounts to add an entry in the columns index.

df_fruits.columnsIndex(['apples', 'oranges', 'bananas'], dtype='object')And we forgot the dates!

df_fruits['time'] = [

"2020/10/08 12:13", "2020/10/07 11:37",

"2020/10/10 14:07", "2020/10/09 10:51"

]

df_fruits| apples | oranges | bananas | time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 2020/10/08 12:13 |

| Sean | NaN | 3 | 2 | 2020/10/07 11:37 |

| Pierce | 0.0 | 7 | 1 | 2020/10/10 14:07 |

| Roger | 1.0 | 2 | 6 | 2020/10/09 10:51 |

df_fruits.dtypesapples float64

oranges int64

bananas int64

time object

dtype: objecttype(df_fruits.loc["Roger", "time"])strIt is not a date but a string (str) ! So we convert this column to something called datetime

df_fruits["time"] = pd.to_datetime(df_fruits["time"])

df_fruits| apples | oranges | bananas | time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 2020-10-08 12:13:00 |

| Sean | NaN | 3 | 2 | 2020-10-07 11:37:00 |

| Pierce | 0.0 | 7 | 1 | 2020-10-10 14:07:00 |

| Roger | 1.0 | 2 | 6 | 2020-10-09 10:51:00 |

df_fruits.dtypesapples float64

oranges int64

bananas int64

time datetime64[ns]

dtype: objectEvery data science framework implements some datetime handling scheme. For Python see Python official documentation on datetime module

Note that datetime64[ns] parallels NumPy datetime64.

What if we want to keep only the baskets after (including) October, 9th ?

df_fruits.loc[df_fruits["time"] >= pd.Timestamp("2020/10/09")]| apples | oranges | bananas | time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pierce | 0.0 | 7 | 1 | 2020-10-10 14:07:00 |

| Roger | 1.0 | 2 | 6 | 2020-10-09 10:51:00 |

We can filter rows using a boolean mask and member loc. This does not work with iloc.

In many circumstances, we have to cast columns to a different type. To convert a Pandas Series to a different data type, we may use the .astype() method:

# Create a sample Series

s = pd.Series([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

s0 1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

dtype: int64# Check the current dtype

s.dtypedtype('int64')If we want to move to float:

# Cast to float

s_float = s.astype('float64')

s_float0 1.0

1 2.0

2 3.0

3 4.0

4 5.0

dtype: float64to strings:

# Cast to string

s_str = s.astype('str')

s_str0 1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

dtype: objectto a categorical type:

# Cast to category

s_cat = s.astype('category')

s_cat0 1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

dtype: category

Categories (5, int64): [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]This also works for bool.

Sometimes, it may go wrong.

When converting types, you may encounter errors if the conversion is not possible:

# This will raise an error if conversion fails

try:

pd.Series(['1', '2', 'abc']).astype('int64')

except ValueError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")Error: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'abc'Then method astype() may not be the best choice. For more robust conversion, use pd.to_numeric() with error handling:

# Convert with error handling - invalid values become NaN

pd.to_numeric(pd.Series(['1', '2', 'abc']), errors='coerce')0 1.0

1 2.0

2 NaN

dtype: float64For datetime conversions, pd.to_datetime() is usually preferred over .astype('datetime64[ns]') as it handles various date formats more robustly.

df_fruits| apples | oranges | bananas | time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 2020-10-08 12:13:00 |

| Sean | NaN | 3 | 2 | 2020-10-07 11:37:00 |

| Pierce | 0.0 | 7 | 1 | 2020-10-10 14:07:00 |

| Roger | 1.0 | 2 | 6 | 2020-10-09 10:51:00 |

df_fruits.loc[:, "oranges":"time"]| oranges | bananas | time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 0 | 0 | 2020-10-08 12:13:00 |

| Sean | 3 | 2 | 2020-10-07 11:37:00 |

| Pierce | 7 | 1 | 2020-10-10 14:07:00 |

| Roger | 2 | 6 | 2020-10-09 10:51:00 |

df_fruits.loc["Daniel":"Sean", "apples":"bananas"]| apples | oranges | bananas | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sean | NaN | 3 | 2 |

If we want to project over a collection of columns, we have to

df_fruits[["apples", "time"]]| apples | time | |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3.0 | 2020-10-08 12:13:00 |

| Sean | NaN | 2020-10-07 11:37:00 |

| Pierce | 0.0 | 2020-10-10 14:07:00 |

| Roger | 1.0 | 2020-10-09 10:51:00 |

tropicals = ("apples", "oranges")

df_fruits[[*tropicals]]| apples | oranges | |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3.0 | 0 |

| Sean | NaN | 3 |

| Pierce | 0.0 | 7 |

| Roger | 1.0 | 2 |

We cannot write:

df_fruits["apples", "time"]Why?

What if we want to write the file ?

df_fruits| apples | oranges | bananas | time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 2020-10-08 12:13:00 |

| Sean | NaN | 3 | 2 | 2020-10-07 11:37:00 |

| Pierce | 0.0 | 7 | 1 | 2020-10-10 14:07:00 |

| Roger | 1.0 | 2 | 6 | 2020-10-09 10:51:00 |

df_fruits.to_csv("fruits.csv")# Use !dir on windows

!ls -alh | grep fru-rw-rw-r-- 1 boucheron boucheron 163 janv. 18 22:07 fruits.csv!head -n 5 fruits.csv,apples,oranges,bananas,time

Daniel,3.0,0,0,2020-10-08 12:13:00

Sean,,3,2,2020-10-07 11:37:00

Pierce,0.0,7,1,2020-10-10 14:07:00

Roger,1.0,2,6,2020-10-09 10:51:00The tips dataset comes through Kaggle

This dataset is a treasure trove of information from a collection of case studies for business statistics. Special thanks to Bryant and Smith for their diligent work:

Bryant, P. G. and Smith, M (1995) Practical Data Analysis: Case Studies in Business Statistics. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin Publishing.

You can also access this dataset now through the Python package Seaborn.

It contains data about a restaurant: the bill, tip and some informations about the customers.

A data pipeline usually starts with Extraction, that is gathering data from some source, possibly in a galaxy far, far awy. Here follows a toy extraction pattern

URL using package requestsimport requests

import os

# The path containing your notebook

path_data = './'

# The name of the file

filename = 'tips.csv'

if os.path.exists(os.path.join(path_data, filename)):

print(f'The file {os.path.join(path_data, filename)} already exists.')

else:

url = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mwaskom/seaborn-data/refs/heads/master/tips.csv'

r = requests.get(url)

with open(os.path.join(path_data, filename), 'wb') as f:

f.write(r.content)

print('Downloaded file %s.' % os.path.join(path_data, filename))df = pd.read_csv(

"tips.csv",

delimiter=","

)The data can be obtained from package seaborn.

import seaborn as sns

sns_ds = sns.get_dataset_names()

'tips' in sns_ds

df = sns.load_dataset('tips')Note that the dataframe loaded from the csv file and the dataframe obtained from package seaborn differ. This can be checked by examining the representations and properties of column smoker, sex (check df.sex.array in both cases)

# `.head()` shows the first rows of the dataframe

df.head(n=10)| total_bill | tip | sex | smoker | day | time | size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 4 |

| 5 | 25.29 | 4.71 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 4 |

| 6 | 8.77 | 2.00 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 7 | 26.88 | 3.12 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 4 |

| 8 | 15.04 | 1.96 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 9 | 14.78 | 3.23 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

df.info()<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 244 entries, 0 to 243

Data columns (total 7 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 total_bill 244 non-null float64

1 tip 244 non-null float64

2 sex 244 non-null category

3 smoker 244 non-null category

4 day 244 non-null category

5 time 244 non-null category

6 size 244 non-null int64

dtypes: category(4), float64(2), int64(1)

memory usage: 7.4 KBdf.loc[42, "day"]'Sun'type(df.loc[42, "day"])strBy default, columns that are non-numerical contain strings (str type)

category typeAn important type in pandas is category for variables that are non-numerical

Pro tip. It’s always a good idea to tell pandas which columns should be imported as categorical

So, let’s read again the file specifying some dtypes to the read_csv function

dtypes = {

"sex": "category",

"smoker": "category",

"day": "category",

"time": "category"

}

df = pd.read_csv("tips.csv", dtype=dtypes)Supplemented with this typing information, the dataframe loaded from the csv file is more like the dataframe obtained from seaborn.

df.dtypestotal_bill float64

tip float64

sex category

smoker category

day category

time category

size int64

dtype: object# The describe method only shows statistics for the numerical columns by default

df.describe()| total_bill | tip | size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| count | 244.000000 | 244.000000 | 244.000000 |

| mean | 19.785943 | 2.998279 | 2.569672 |

| std | 8.902412 | 1.383638 | 0.951100 |

| min | 3.070000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| 25% | 13.347500 | 2.000000 | 2.000000 |

| 50% | 17.795000 | 2.900000 | 2.000000 |

| 75% | 24.127500 | 3.562500 | 3.000000 |

| max | 50.810000 | 10.000000 | 6.000000 |

# We use the include="all" option to see everything

df.describe(include="all")| total_bill | tip | sex | smoker | day | time | size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 244.000000 | 244.000000 | 244 | 244 | 244 | 244 | 244.000000 |

| unique | NaN | NaN | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | NaN |

| top | NaN | NaN | Male | No | Sat | Dinner | NaN |

| freq | NaN | NaN | 157 | 151 | 87 | 176 | NaN |

| mean | 19.785943 | 2.998279 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2.569672 |

| std | 8.902412 | 1.383638 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 0.951100 |

| min | 3.070000 | 1.000000 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 1.000000 |

| 25% | 13.347500 | 2.000000 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2.000000 |

| 50% | 17.795000 | 2.900000 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2.000000 |

| 75% | 24.127500 | 3.562500 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 3.000000 |

| max | 50.810000 | 10.000000 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 6.000000 |

# Correlation between the numerical columns

df.corr(numeric_only = True)| total_bill | tip | size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| total_bill | 1.000000 | 0.675734 | 0.598315 |

| tip | 0.675734 | 1.000000 | 0.489299 |

| size | 0.598315 | 0.489299 | 1.000000 |

In more general settings, to select only numerical columns from a DataFrame, use the select_dtypes() method:

# Select only numerical columns (int, float, etc.)

(

df

.select_dtypes(include=['number'])

.head()

)| total_bill | tip | size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | 2 |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | 3 |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | 3 |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | 2 |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | 4 |

The select_dtypes() method is very flexible: - include=['number'] selects all numeric types (int, float, etc.) - include=['int64', 'float64'] selects specific dtypes - exclude=['object'] excludes string columns - You can combine include and exclude parameters

(

df

.select_dtypes(include='float64')

.corr()

)| total_bill | tip | |

|---|---|---|

| total_bill | 1.000000 | 0.675734 |

| tip | 0.675734 | 1.000000 |

Pandas DataFrames have built-in plotting capabilities through the .plot accessor. By default, Pandas uses matplotlib as the plotting backend.

You can set the plotting backend using pd.options.plotting.backend:

# Set the backend globally for all DataFrames

pd.options.plotting.backend = 'matplotlib' # defaultAvailable backends include:

'matplotlib' (default)'plotly' (requires plotly package)'hvplot' (requires hvplot package)Seaborn is not available as a plotting backend for pd.options.plotting.backend. Seaborn is a separate visualization library built on top of matplotlib that works directly with pandas DataFrames through its own API (e.g., sns.scatterplot(data=df, ...)). While seaborn integrates seamlessly with pandas DataFrames, it doesn’t replace the .plot accessor’s backend system.

# Default matplotlib backend

pd.options.plotting.backend = 'matplotlib'

df.plot.scatter(x='total_bill', y='tip')

# Switch to plotly for interactive plots

pd.options.plotting.backend = 'plotly'

df.plot.scatter(x='total_bill', y='tip') # Now creates an interactive plotly plotYou can also specify the backend for a specific plot without changing the global setting:

# Use a specific backend for one plot only

df.plot(backend='plotly', kind='scatter', x='total_bill', y='tip')pip install plotly for plotly backend)matplotlib backend is always available and is the defaultmatplotlib and seabornLet’s show how we can use matplotlib and seaborn to visualize data contained in a pandas dataframe

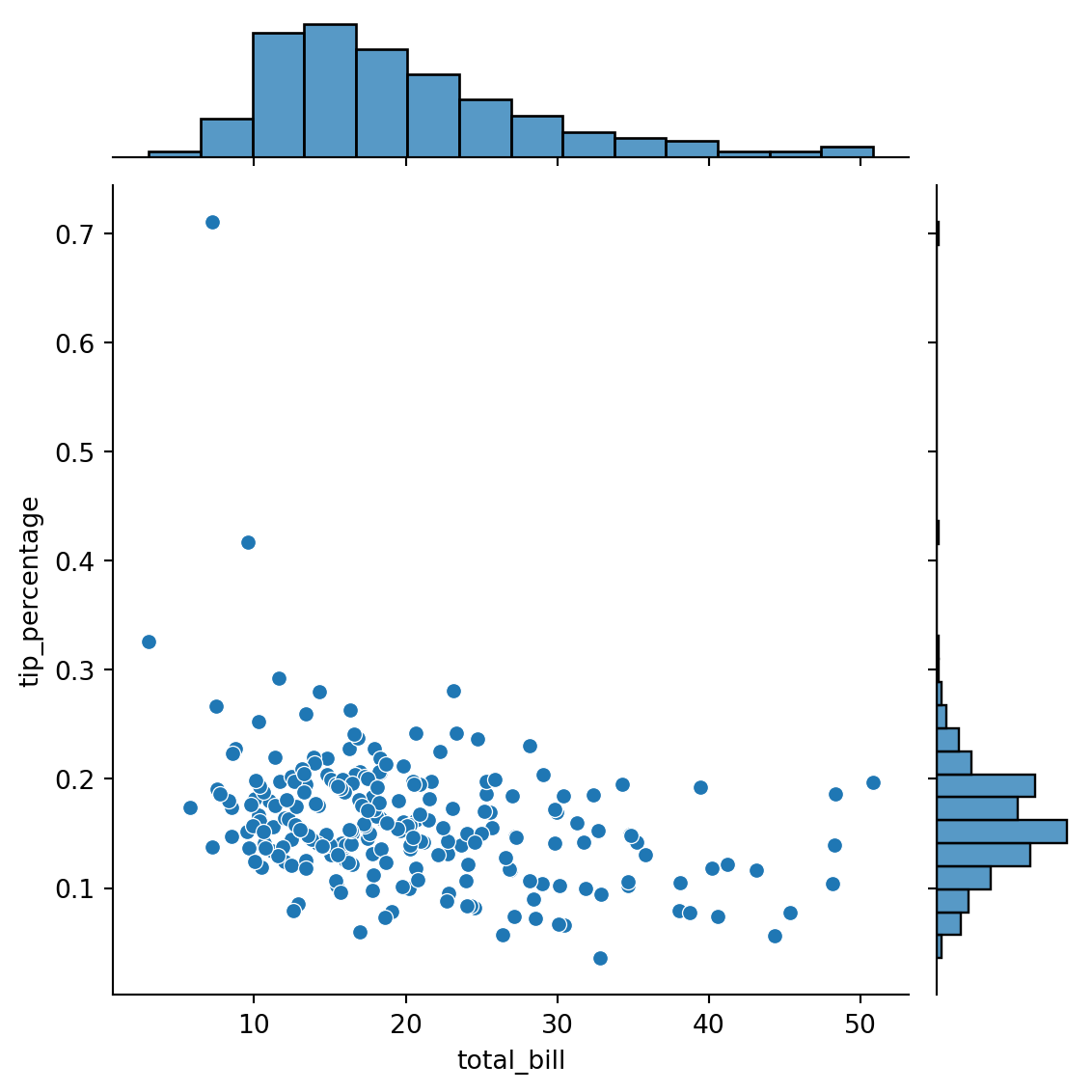

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltsns.jointplot(x="total_bill", y="tip", data=df)

A jointplot (as in seaborn) is an enriched scatterplot with histograms on both axes.

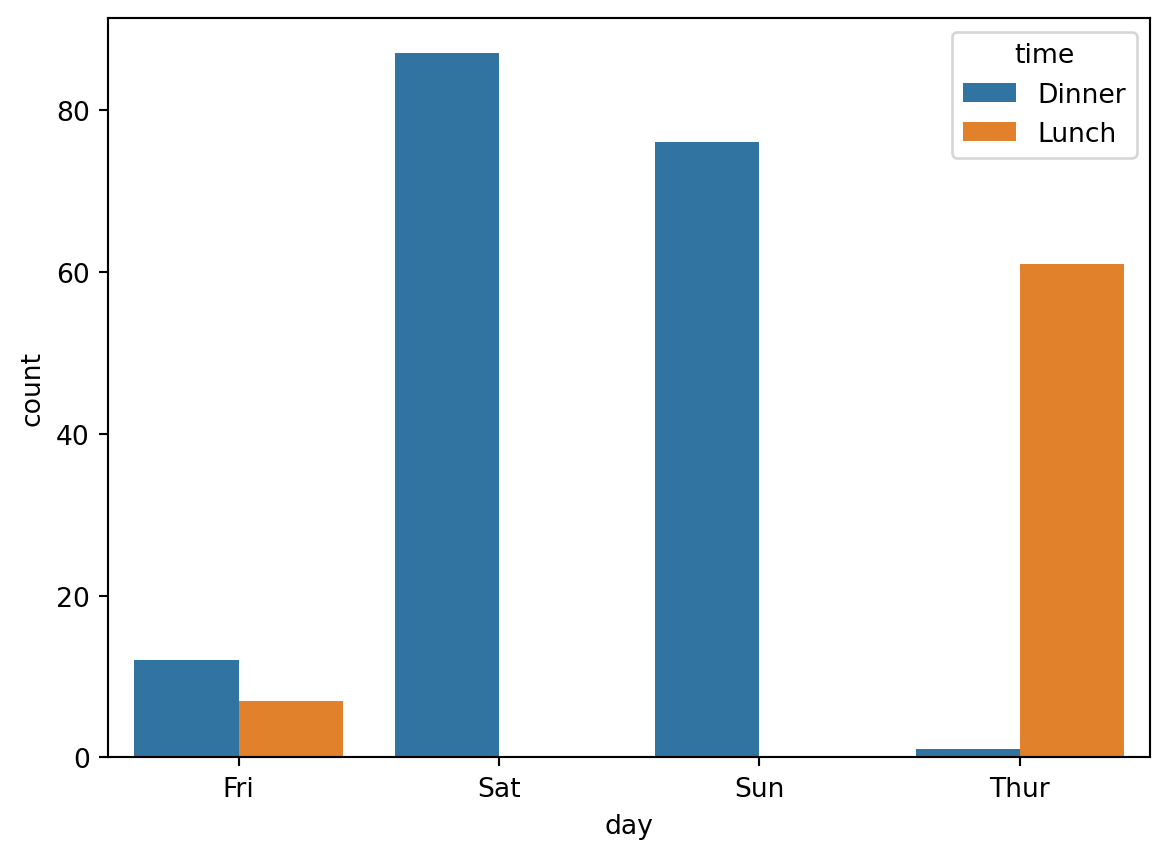

sns.countplot(x='day', hue="time", data=df)

This is also called a barplot.

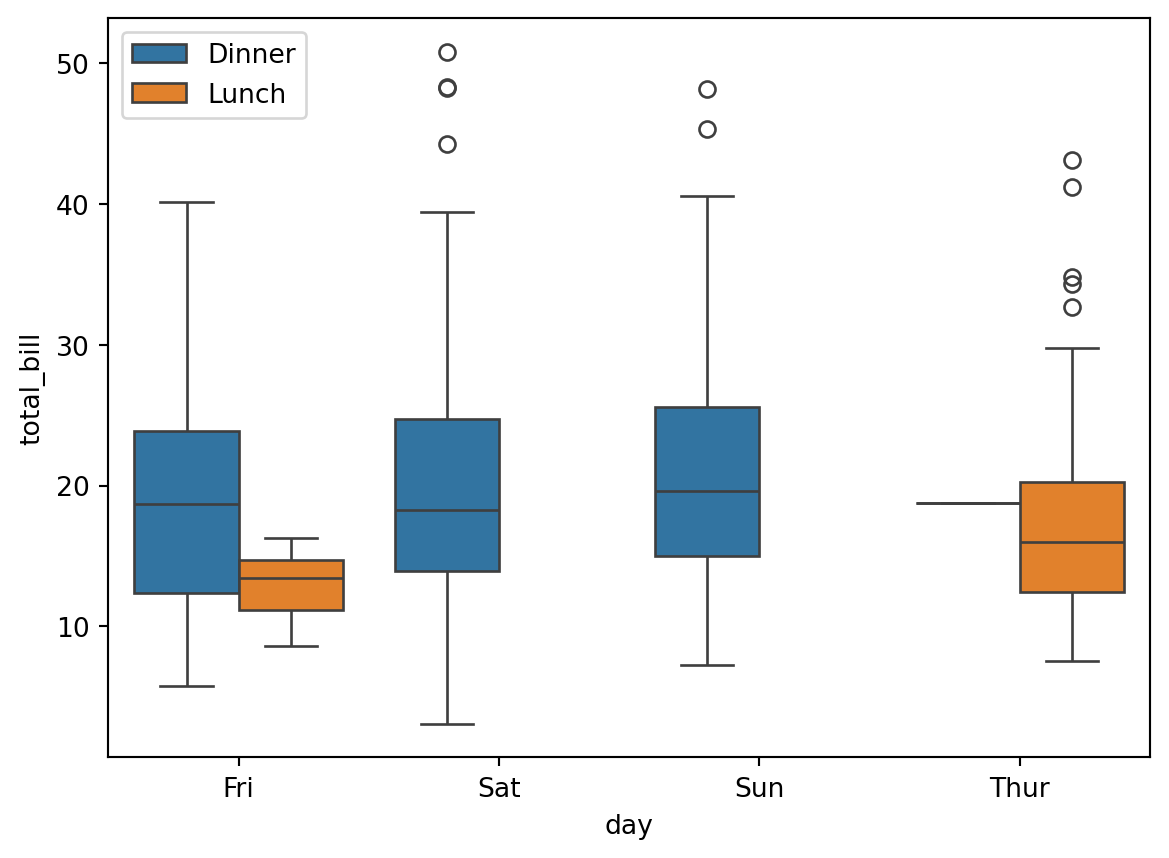

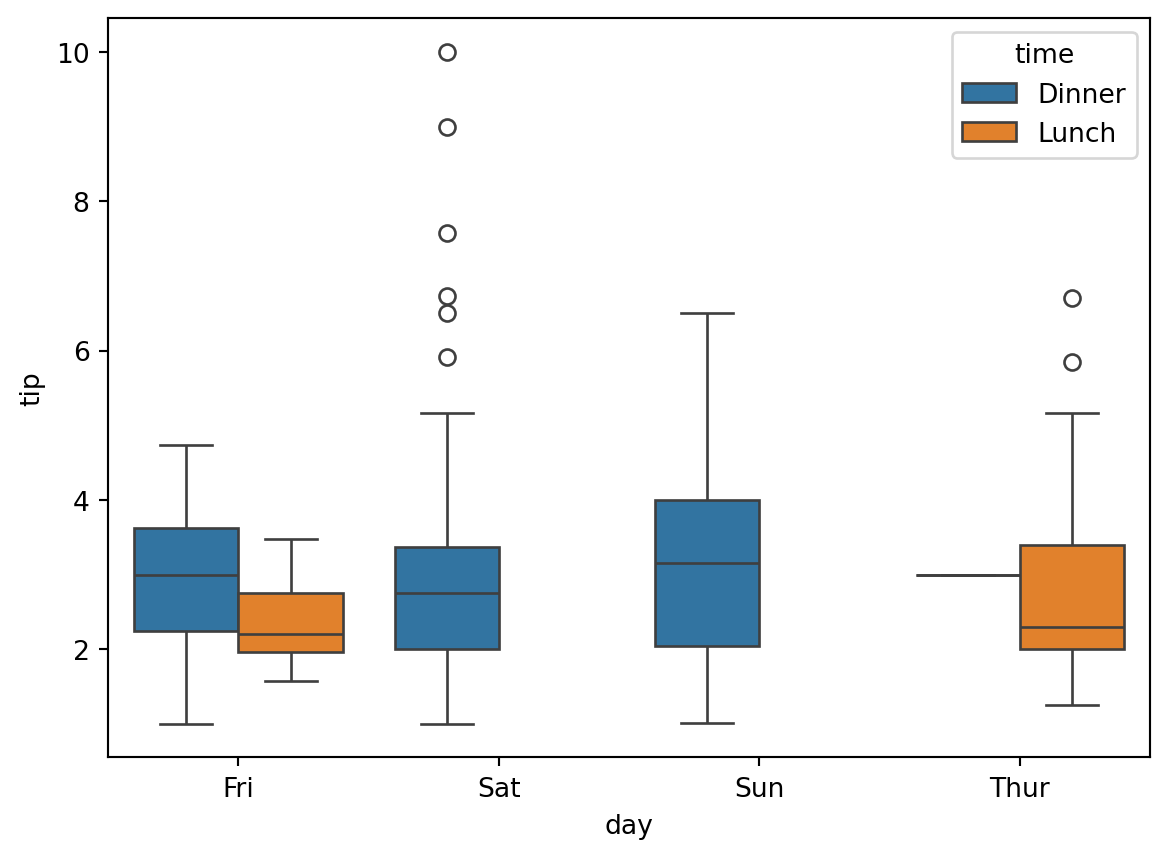

plt.figure(figsize=(7, 5))

sns.boxplot(x='day', y='total_bill', hue='time', data=df)

plt.legend(loc="upper left")

boxplot (box and whiskers plot) are used to sketch empirical distributions and to display summary statistics (median and quartiles).

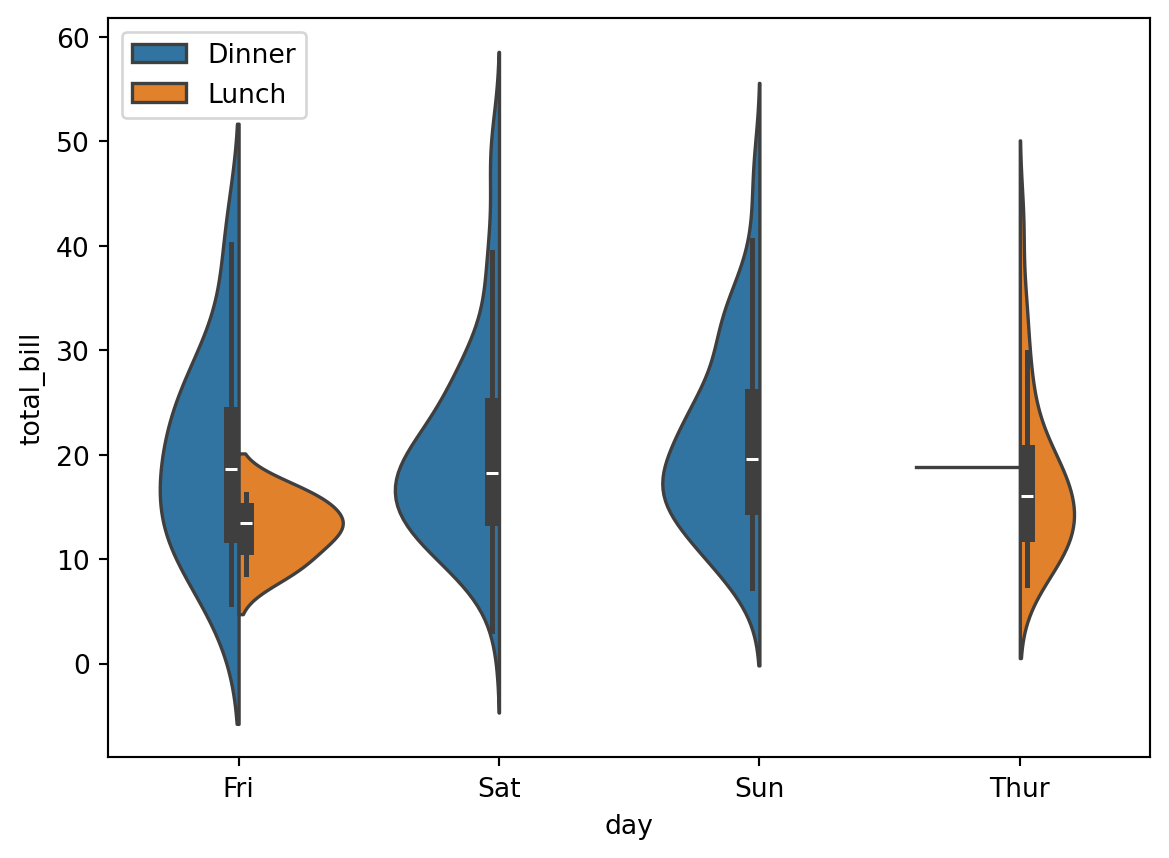

plt.figure(figsize=(7, 5))

sns.violinplot(x='day', y='total_bill', hue='time', split=True, data=df)

plt.legend(loc="upper left")

violinplot are sketchy variants of kernel density estimates.

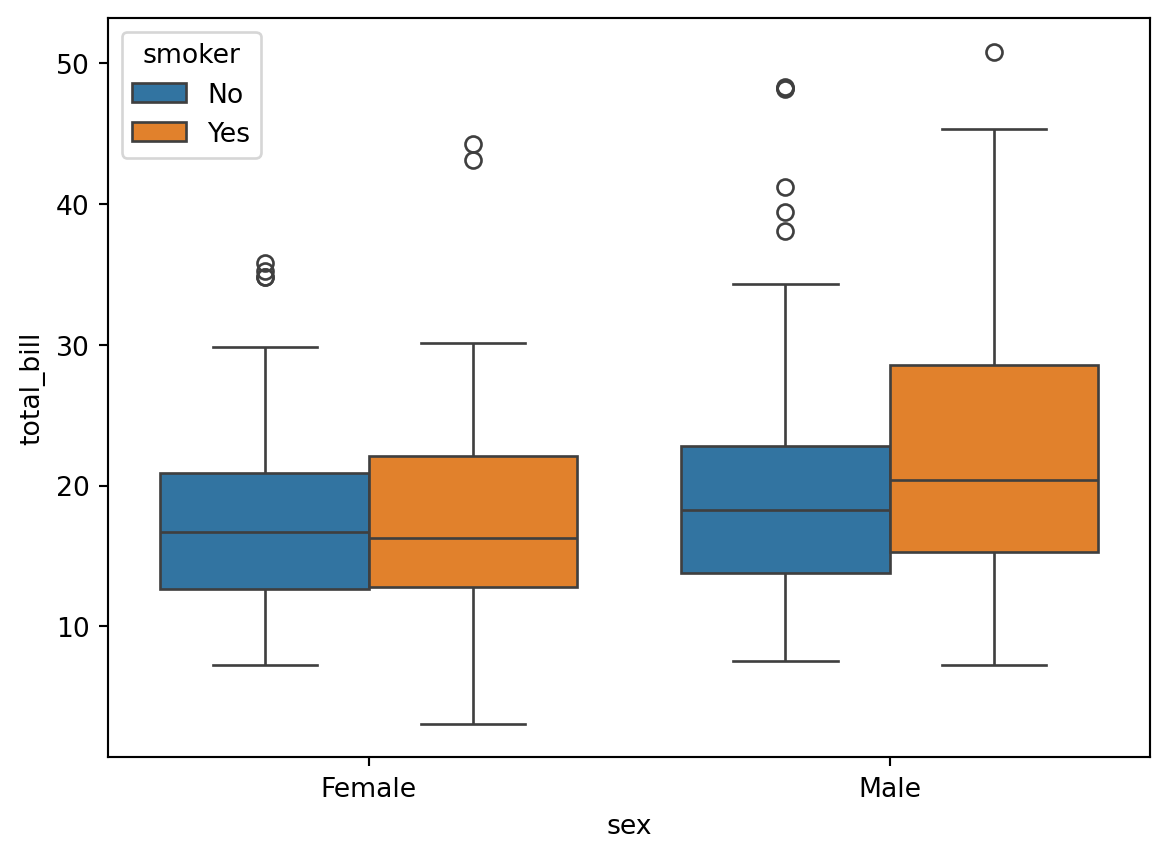

sns.boxplot(x='sex', y='total_bill', hue='smoker', data=df)

sns.boxplot(x='day', y='tip', hue='time', data=df)

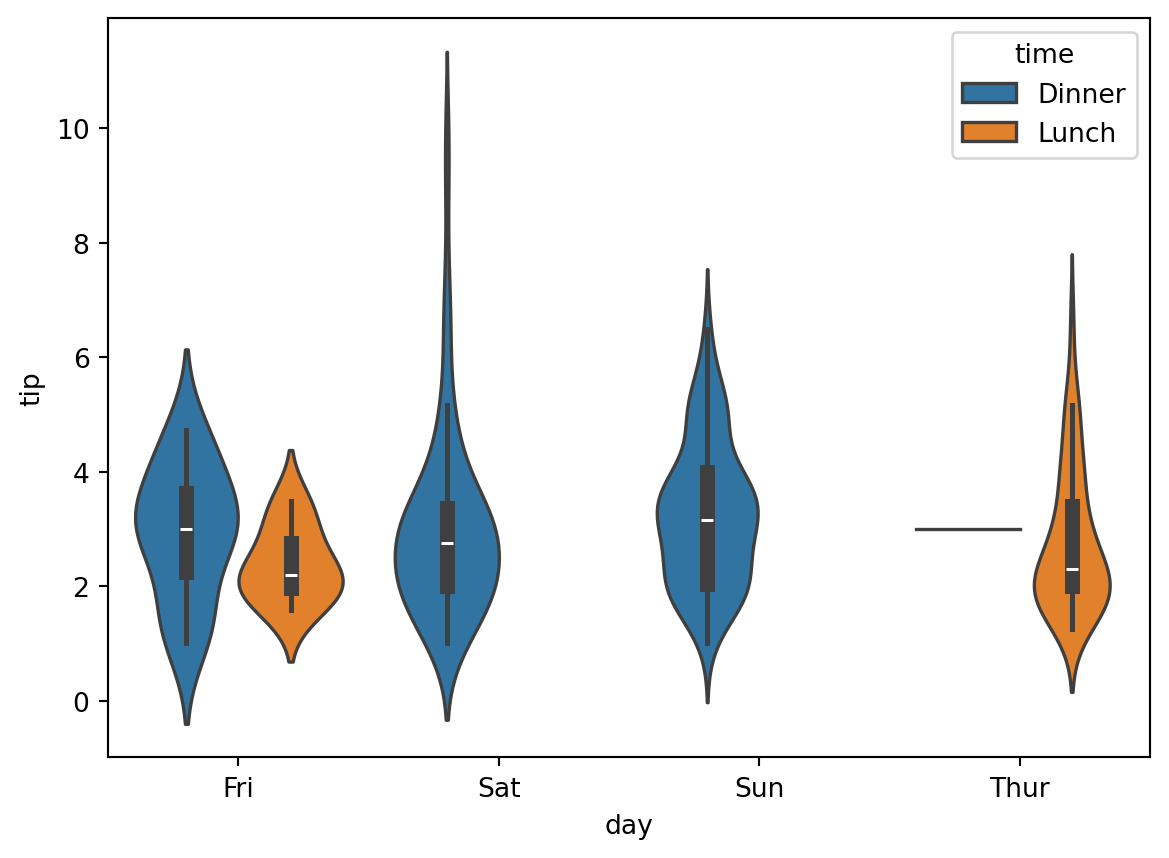

sns.violinplot(x='day', y='tip', hue='time', data=df)

pandasLet us read again the tips.csv file

import pandas as pd

dtypes = {

"sex": "category",

"smoker": "category",

"day": "category",

"time": "category"

}

df = pd.read_csv("tips.csv", dtype=dtypes)

df.head()| total_bill | tip | sex | smoker | day | time | size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 4 |

pandas : broadcastingLet’s add a column that contains the tip percentage. The content of this column is computed by performing elementwise operations between elements of two columns. This works as if the columns were NumPy arrays (even though they are not).

df["tip_percentage"] = df["tip"] / df["total_bill"]

df.head()| total_bill | tip | sex | smoker | day | time | size | tip_percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 | 0.059447 |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 | 0.160542 |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 | 0.166587 |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 | 0.139780 |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 4 | 0.146808 |

The computation

```{python}

df["tip"] / df["total_bill"]

```uses a broadcast rule (see NumPy notebook about broadcasting).

numpy arrays, Series or pandas dataframes when the computation makes sense in view of their respective shapeThis principle is called broadcast or broadcasting.

Broadcasting is a key feature of numpy ndarray, see

df["tip"].shape, df["total_bill"].shape((244,), (244,))The tip and total_billcolumns have the same shape, so broadcasting performs pairwise division.

This corresponds to the following “hand-crafted” approach with a for loop:

#|

for i in range(df.shape[0]):

df.loc[i, "tip_percentage"] = df.loc[i, "tip"] / df.loc[i, "total_bill"]But using such a loop is:

NEVER use Python for-loops unless you need to !

%%timeit -n 10

for i in range(df.shape[0]):

df.loc[i, "tip_percentage"] = df.loc[i, "tip"] / df.loc[i, "total_bill"]23.5 ms ± 133 μs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)%%timeit -n 10

df["tip_percentage"] = df["tip"] / df["total_bill"]67.9 μs ± 12.3 μs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)The for loop is \(\approx\) 100 times slower ! (even worse on larger data)

DataFrameWhen you want to change a value in a DataFrame, never use

df["tip_percentage"].loc[i] = 42but use

df.loc[i, "tip_percentage"] = 42Use a single loc or iloc statement. The first version might not work: it might modify a copy of the column and not the dataframe itself !

Another example of broadcasting is:

(100 * df[["tip_percentage"]]).head()| tip_percentage | |

|---|---|

| 0 | 5.944673 |

| 1 | 16.054159 |

| 2 | 16.658734 |

| 3 | 13.978041 |

| 4 | 14.680765 |

where we multiplied each entry of the tip_percentage column by 100.

Note the difference between

df[['tip_percentage']]which returns a DataFrame containing only the tip_percentage column and

df['tip_percentage']which returns a Series containing the data of the tip_percentage column

sns.jointplot(

x="total_bill",

y="tip_percentage",

data=df

)

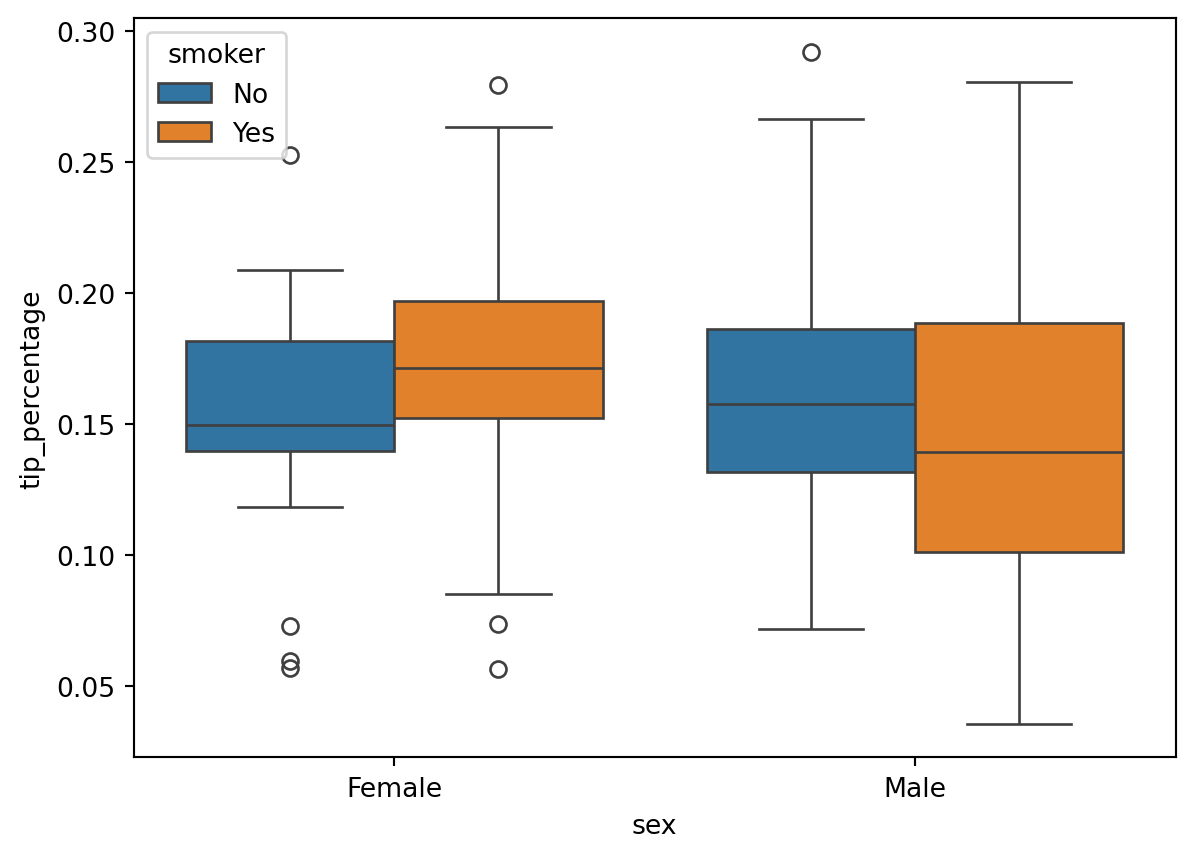

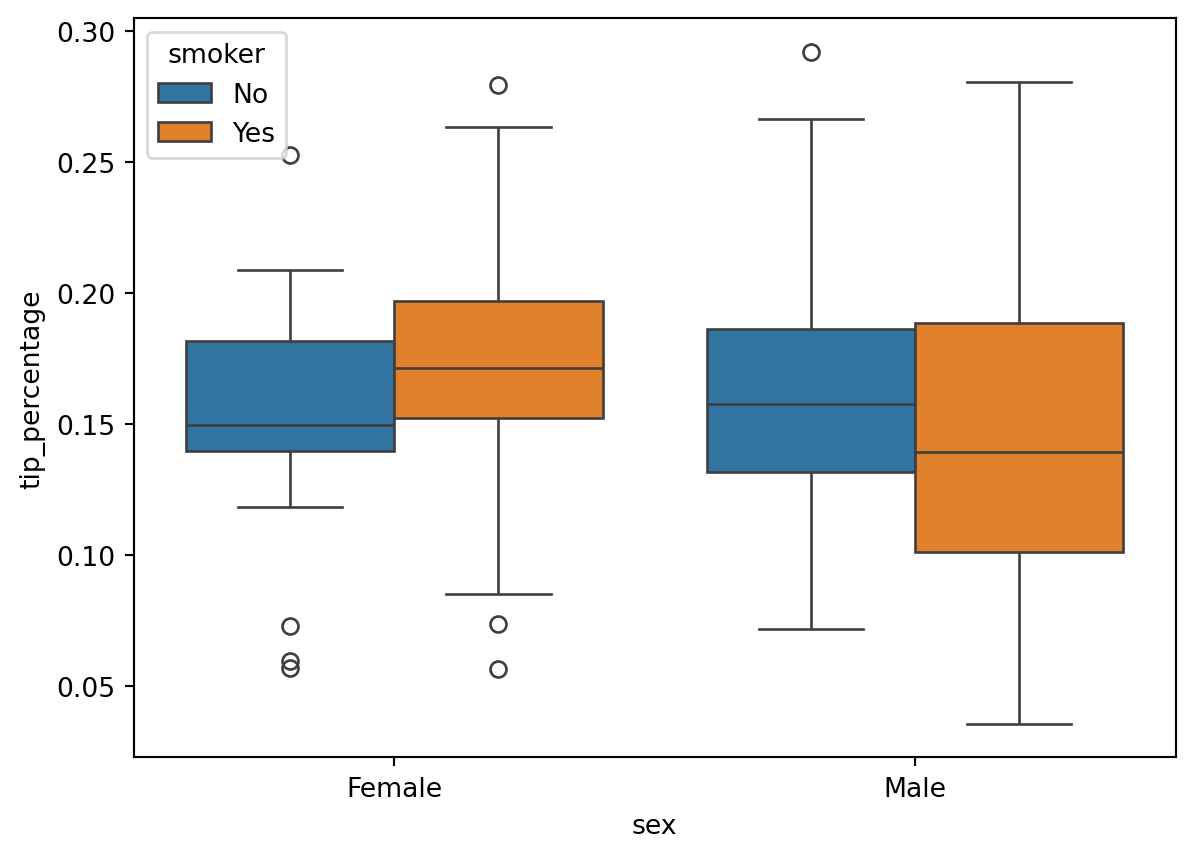

sns.boxplot(

x='sex',

y='tip_percentage',

hue='smoker',

data=df

)

tip_percentage outliers ?sns.boxplot(

x='sex',

y='tip_percentage',

hue='smoker',

data=df.loc[df["tip_percentage"] <= 0.3]

)

Object identity

id(df)123374907814880groupby and aggregateMany computations can be formulated as a groupby followed by and aggregation.

tip and tip percentage each day ?df.head()| total_bill | tip | sex | smoker | day | time | size | tip_percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 | 0.059447 |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 | 0.160542 |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 | 0.166587 |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 | 0.139780 |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 4 | 0.146808 |

try:

(

df

.groupby("day", observed=True)

.mean()

)

except TypeError:

print('TypeError: category dtype does not support aggregation "mean"')TypeError: category dtype does not support aggregation "mean"But we do not care about the size column here, so we can use instead

(

df[["total_bill", "tip", "tip_percentage", "day"]]

.groupby("day")

.mean()

)/tmp/ipykernel_67207/1740663163.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| total_bill | tip | tip_percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| day | |||

| Fri | 17.151579 | 2.734737 | 0.169913 |

| Sat | 20.441379 | 2.993103 | 0.153152 |

| Sun | 21.410000 | 3.255132 | 0.166897 |

| Thur | 17.682742 | 2.771452 | 0.161276 |

If we want to be more precise, we can groupby using several columns

(

df[["total_bill", "tip", "tip_percentage", "day", "time"]] # selection

.groupby(["day","time"]) # partition

.mean() # aggregation

)/tmp/ipykernel_67207/391063870.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| total_bill | tip | tip_percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| day | time | |||

| Fri | Dinner | 19.663333 | 2.940000 | 0.158916 |

| Lunch | 12.845714 | 2.382857 | 0.188765 | |

| Sat | Dinner | 20.441379 | 2.993103 | 0.153152 |

| Lunch | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Sun | Dinner | 21.410000 | 3.255132 | 0.166897 |

| Lunch | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| Thur | Dinner | 18.780000 | 3.000000 | 0.159744 |

| Lunch | 17.664754 | 2.767705 | 0.161301 |

DataFrame with a two-level indexing: on the day and the timeNaN values for empty groups (e.g. Sat, Lunch)Sometimes, it is more convenient to get the groups as columns instead of a multi-level index.

For this, use reset_index:

(

df[["total_bill", "tip", "tip_percentage", "day", "time"]] # selection

.groupby(["day", "time"]) # partition

.mean() # aggregation

.reset_index() # ako ungroup

)/tmp/ipykernel_67207/835267922.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| day | time | total_bill | tip | tip_percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Fri | Dinner | 19.663333 | 2.940000 | 0.158916 |

| 1 | Fri | Lunch | 12.845714 | 2.382857 | 0.188765 |

| 2 | Sat | Dinner | 20.441379 | 2.993103 | 0.153152 |

| 3 | Sat | Lunch | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 4 | Sun | Dinner | 21.410000 | 3.255132 | 0.166897 |

| 5 | Sun | Lunch | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 6 | Thur | Dinner | 18.780000 | 3.000000 | 0.159744 |

| 7 | Thur | Lunch | 17.664754 | 2.767705 | 0.161301 |

Computations with pandas can include many operations that are pipelined until the final computation.

Pipelining many operations is good practice and perfectly normal, but in order to make the code readable you can put it between parenthesis (python expression) as follows:

(

df[["total_bill", "tip", "tip_percentage", "day", "time"]]

.groupby(["day", "time"])

.mean()

.reset_index()

# and on top of all this we sort the dataframe with respect

# to the tip_percentage

.sort_values("tip_percentage")

)/tmp/ipykernel_67207/45053252.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| day | time | total_bill | tip | tip_percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Sat | Dinner | 20.441379 | 2.993103 | 0.153152 |

| 0 | Fri | Dinner | 19.663333 | 2.940000 | 0.158916 |

| 6 | Thur | Dinner | 18.780000 | 3.000000 | 0.159744 |

| 7 | Thur | Lunch | 17.664754 | 2.767705 | 0.161301 |

| 4 | Sun | Dinner | 21.410000 | 3.255132 | 0.166897 |

| 1 | Fri | Lunch | 12.845714 | 2.382857 | 0.188765 |

| 3 | Sat | Lunch | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 5 | Sun | Lunch | NaN | NaN | NaN |

DataFrame with styleNow, we can answer, with style, to the question: what are the average tip percentages along the week ?

(

df[["tip_percentage", "day", "time"]]

.groupby(["day", "time"])

.mean()

# At the end of the pipeline you can use .style

.style

# Print numerical values as percentages

.format("{:.2%}")

.background_gradient()

)/tmp/ipykernel_67207/838795167.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| tip_percentage | ||

|---|---|---|

| day | time | |

| Fri | Dinner | 15.89% |

| Lunch | 18.88% | |

| Sat | Dinner | 15.32% |

| Lunch | nan% | |

| Sun | Dinner | 16.69% |

| Lunch | nan% | |

| Thur | Dinner | 15.97% |

| Lunch | 16.13% |

NaN valuesBut the NaN values are somewhat annoying. Let’s remove them

(

df[["tip_percentage", "day", "time"]]

.groupby(["day", "time"])

.mean()

# We just add this from the previous pipeline

.dropna()

.style

.format("{:.2%}")

.background_gradient()

)/tmp/ipykernel_67207/2662169510.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| tip_percentage | ||

|---|---|---|

| day | time | |

| Fri | Dinner | 15.89% |

| Lunch | 18.88% | |

| Sat | Dinner | 15.32% |

| Sun | Dinner | 16.69% |

| Thur | Dinner | 15.97% |

| Lunch | 16.13% |

Now, we see when tip_percentage is maximal. But what about the standard deviation?

.mean() for now, but we can use several aggregating function using .agg()(

df[["tip_percentage", "day", "time"]]

.groupby(["day", "time"])

.agg(["mean", "std"]) # we feed `agg` with a list of names of callables

.dropna()

.style

.format("{:.2%}")

.background_gradient()

)/tmp/ipykernel_67207/3957220442.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| tip_percentage | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| mean | std | ||

| day | time | ||

| Fri | Dinner | 15.89% | 4.70% |

| Lunch | 18.88% | 4.59% | |

| Sat | Dinner | 15.32% | 5.13% |

| Sun | Dinner | 16.69% | 8.47% |

| Thur | Lunch | 16.13% | 3.90% |

And we can use also .describe() as aggregation function. Moreover we - use the subset option to specify which column we want to style - we use ("tip_percentage", "count") to access multi-level index

(

df[["tip_percentage", "day", "time"]]

.groupby(["day", "time"])

.describe() # all-purpose summarising function

)/tmp/ipykernel_67207/3924876303.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| tip_percentage | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | mean | std | min | 25% | 50% | 75% | max | ||

| day | time | ||||||||

| Fri | Dinner | 12.0 | 0.158916 | 0.047024 | 0.103555 | 0.123613 | 0.144742 | 0.179199 | 0.263480 |

| Lunch | 7.0 | 0.188765 | 0.045885 | 0.117735 | 0.167289 | 0.187735 | 0.210996 | 0.259314 | |

| Sat | Dinner | 87.0 | 0.153152 | 0.051293 | 0.035638 | 0.123863 | 0.151832 | 0.188271 | 0.325733 |

| Sun | Dinner | 76.0 | 0.166897 | 0.084739 | 0.059447 | 0.119982 | 0.161103 | 0.187889 | 0.710345 |

| Thur | Dinner | 1.0 | 0.159744 | NaN | 0.159744 | 0.159744 | 0.159744 | 0.159744 | 0.159744 |

| Lunch | 61.0 | 0.161301 | 0.038972 | 0.072961 | 0.137741 | 0.153846 | 0.193424 | 0.266312 | |

(

df[["tip_percentage", "day", "time"]]

.groupby(["day", "time"])

.describe()

.dropna()

.style

.bar(subset=[("tip_percentage", "count")])

.background_gradient(subset=[("tip_percentage", "50%")])

)/tmp/ipykernel_67207/673231177.py:3: FutureWarning:

The default of observed=False is deprecated and will be changed to True in a future version of pandas. Pass observed=False to retain current behavior or observed=True to adopt the future default and silence this warning.

| tip_percentage | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | mean | std | min | 25% | 50% | 75% | max | ||

| day | time | ||||||||

| Fri | Dinner | 12.000000 | 0.158916 | 0.047024 | 0.103555 | 0.123613 | 0.144742 | 0.179199 | 0.263480 |

| Lunch | 7.000000 | 0.188765 | 0.045885 | 0.117735 | 0.167289 | 0.187735 | 0.210996 | 0.259314 | |

| Sat | Dinner | 87.000000 | 0.153152 | 0.051293 | 0.035638 | 0.123863 | 0.151832 | 0.188271 | 0.325733 |

| Sun | Dinner | 76.000000 | 0.166897 | 0.084739 | 0.059447 | 0.119982 | 0.161103 | 0.187889 | 0.710345 |

| Thur | Lunch | 61.000000 | 0.161301 | 0.038972 | 0.072961 | 0.137741 | 0.153846 | 0.193424 | 0.266312 |

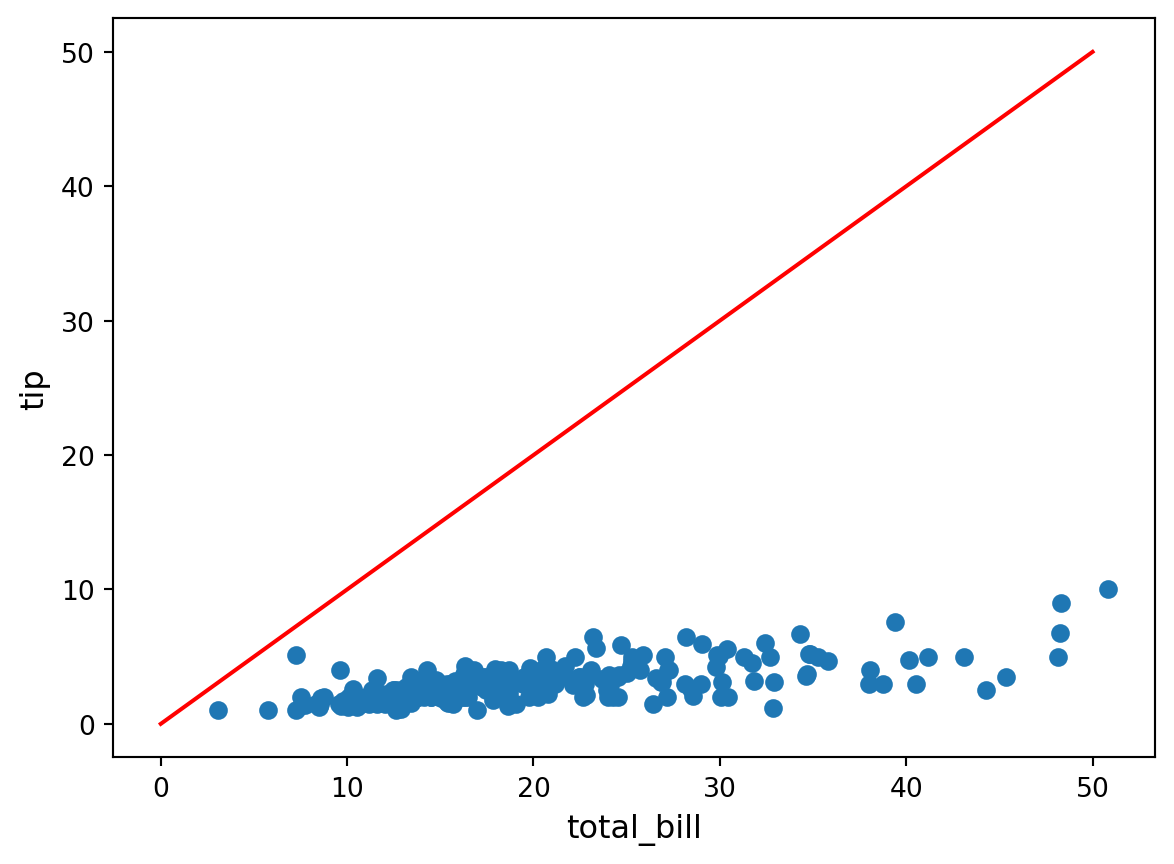

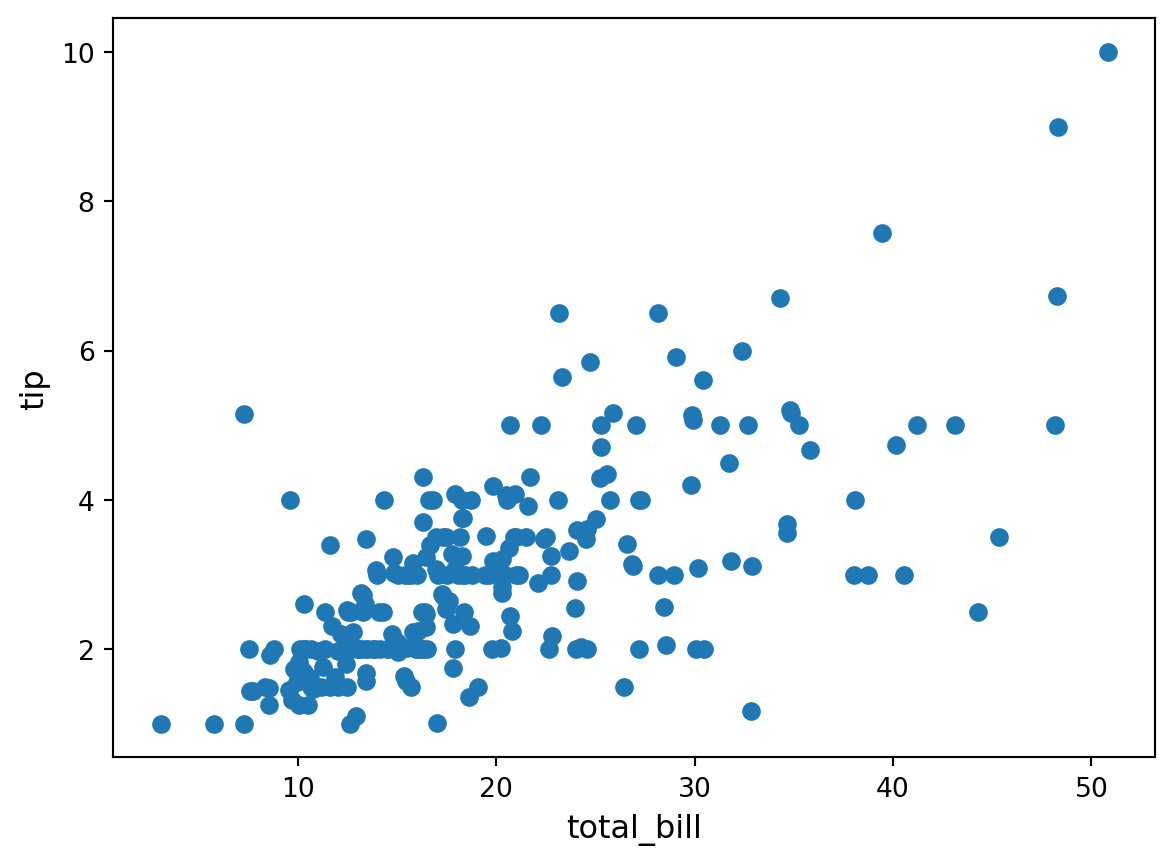

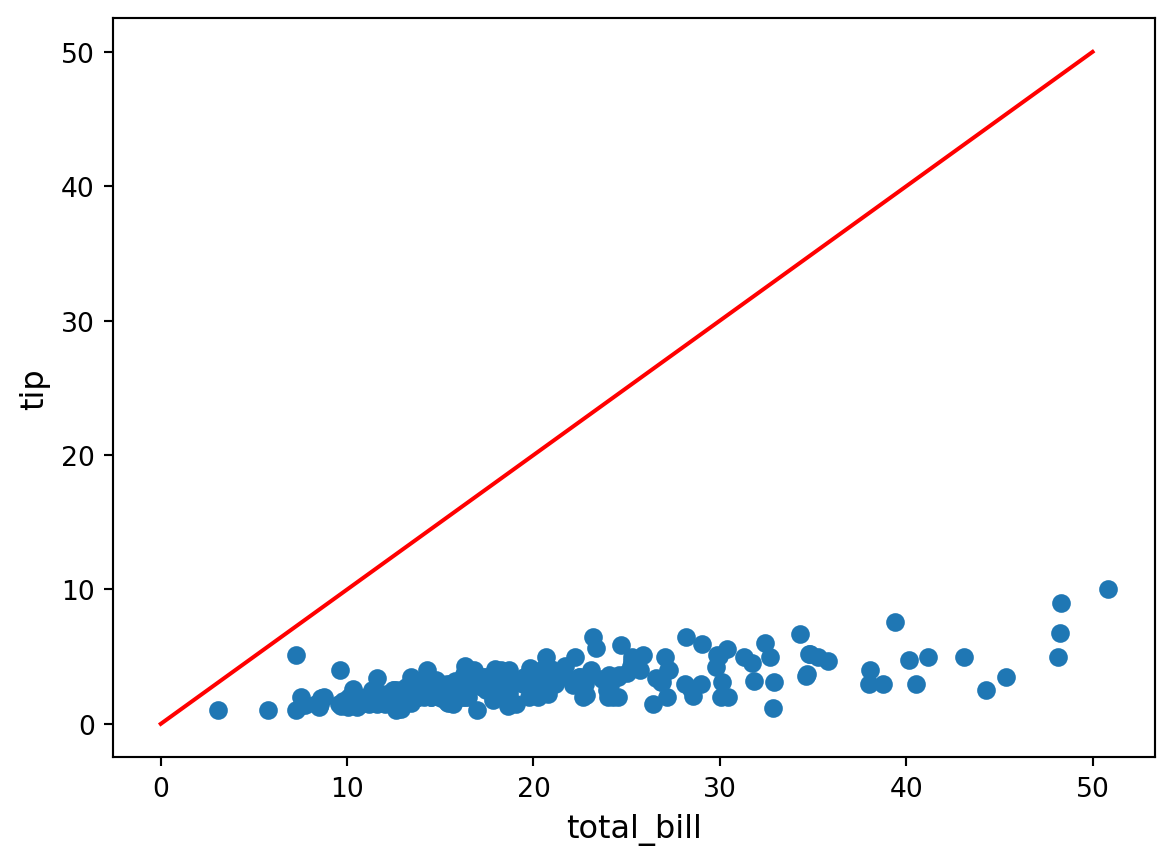

tip based on the total_billAs an example of very simple machine-learning problem, let us try to understand how we can predict tip based on total_bill.

import numpy as np

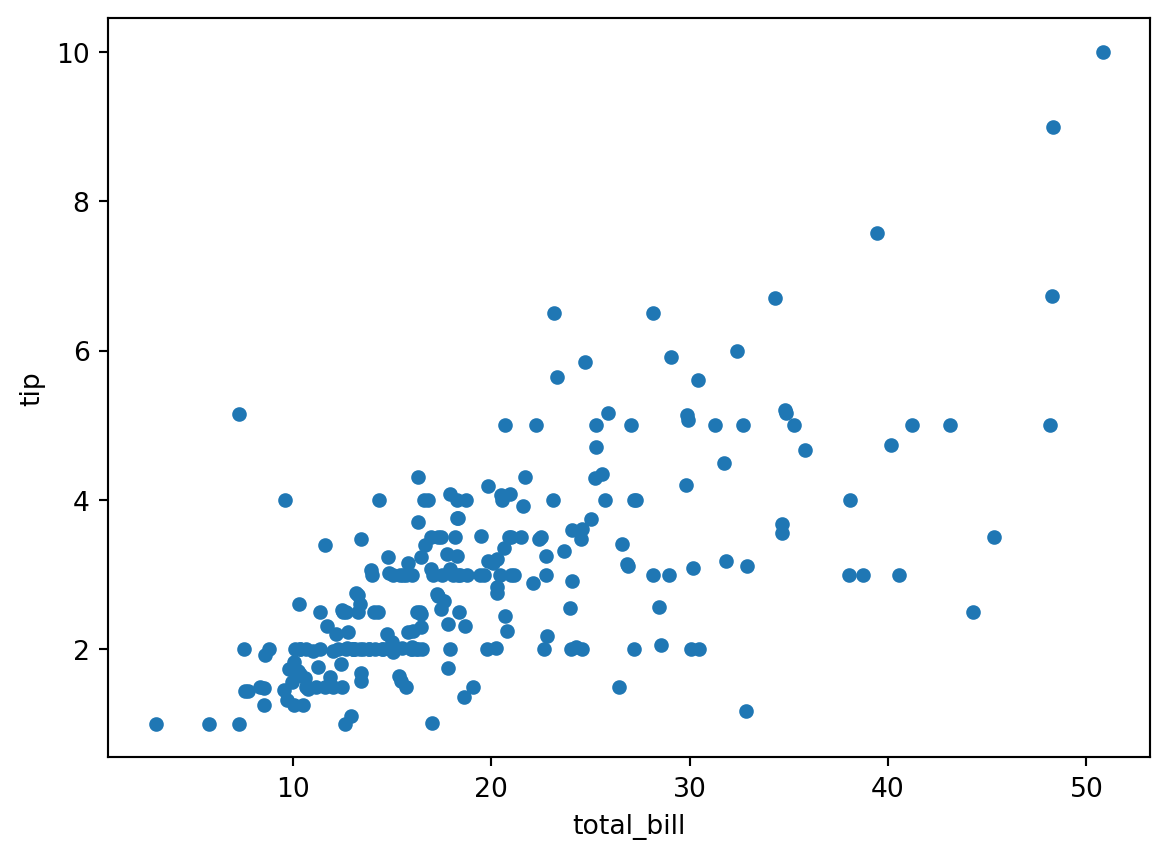

plt.scatter(df["total_bill"], df["tip"])

plt.xlabel("total_bill", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("tip", fontsize=12)Text(0, 0.5, 'tip')

There’s a rough linear dependence between the two. Let us try to find it by hand!

Namely, we look for numbers \(b\) and \(w\) such that

tip ≈ b + w × total_billfor all the examples of pairs of (tip, total_bill) we observe in the data.

In machine learning, we say that this is a very simple example of a supervised learning problem (here it is a regression problem), where tip is the label and where total_bill is the (only) feature, for which we intend to use a linear predictor.

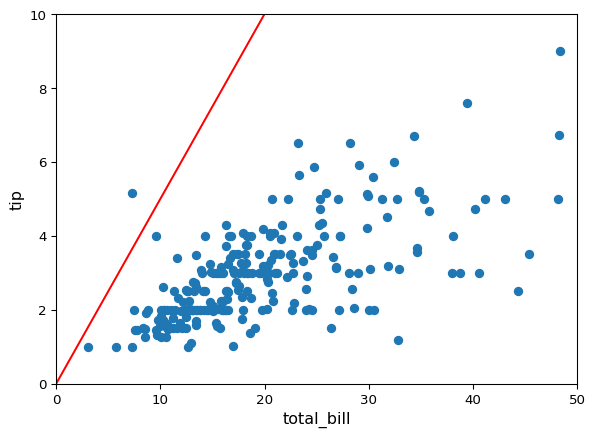

plt.scatter(df["total_bill"], df["tip"])

plt.xlabel("total_bill", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("tip", fontsize=12)

slope = 1.0

intercept = 0.0

x = np.linspace(0, 50, 1000)

plt.plot(x, intercept + slope * x, color="red")

This might require

!pip install ipymplRequirement already satisfied: ipympl in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (0.9.5)

Requirement already satisfied: ipython<9 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipympl) (8.31.0)

Requirement already satisfied: ipywidgets<9,>=7.6.0 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipympl) (8.1.5)

Requirement already satisfied: matplotlib<4,>=3.4.0 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipympl) (3.10.0)

Requirement already satisfied: numpy in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipympl) (2.4.0)

Requirement already satisfied: pillow in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipympl) (11.0.0)

Requirement already satisfied: traitlets<6 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipympl) (5.14.3)

Requirement already satisfied: decorator in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipython<9->ipympl) (5.1.1)

Requirement already satisfied: jedi>=0.16 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipython<9->ipympl) (0.19.2)

Requirement already satisfied: matplotlib-inline in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipython<9->ipympl) (0.1.7)

Requirement already satisfied: pexpect>4.3 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipython<9->ipympl) (4.9.0)

Requirement already satisfied: prompt_toolkit<3.1.0,>=3.0.41 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipython<9->ipympl) (3.0.48)

Requirement already satisfied: pygments>=2.4.0 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipython<9->ipympl) (2.18.0)

Requirement already satisfied: stack_data in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipython<9->ipympl) (0.6.3)

Requirement already satisfied: comm>=0.1.3 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipywidgets<9,>=7.6.0->ipympl) (0.2.2)

Requirement already satisfied: widgetsnbextension~=4.0.12 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipywidgets<9,>=7.6.0->ipympl) (4.0.13)

Requirement already satisfied: jupyterlab-widgets~=3.0.12 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from ipywidgets<9,>=7.6.0->ipympl) (3.0.16)

Requirement already satisfied: contourpy>=1.0.1 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from matplotlib<4,>=3.4.0->ipympl) (1.3.1)

Requirement already satisfied: cycler>=0.10 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from matplotlib<4,>=3.4.0->ipympl) (0.12.1)

Requirement already satisfied: fonttools>=4.22.0 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from matplotlib<4,>=3.4.0->ipympl) (4.55.3)

Requirement already satisfied: kiwisolver>=1.3.1 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from matplotlib<4,>=3.4.0->ipympl) (1.4.8)

Requirement already satisfied: packaging>=20.0 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from matplotlib<4,>=3.4.0->ipympl) (24.2)

Requirement already satisfied: pyparsing>=2.3.1 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from matplotlib<4,>=3.4.0->ipympl) (3.2.1)

Requirement already satisfied: python-dateutil>=2.7 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from matplotlib<4,>=3.4.0->ipympl) (2.9.0.post0)

Requirement already satisfied: wcwidth in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from prompt_toolkit<3.1.0,>=3.0.41->ipython<9->ipympl) (0.2.13)

Requirement already satisfied: parso<0.9.0,>=0.8.4 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from jedi>=0.16->ipython<9->ipympl) (0.8.4)

Requirement already satisfied: ptyprocess>=0.5 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from pexpect>4.3->ipython<9->ipympl) (0.7.0)

Requirement already satisfied: six>=1.5 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from python-dateutil>=2.7->matplotlib<4,>=3.4.0->ipympl) (1.17.0)

Requirement already satisfied: executing>=1.2.0 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from stack_data->ipython<9->ipympl) (2.1.0)

Requirement already satisfied: asttokens>=2.1.0 in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from stack_data->ipython<9->ipympl) (3.0.0)

Requirement already satisfied: pure-eval in /home/boucheron/Documents/IFEBY310/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages (from stack_data->ipython<9->ipympl) (0.2.3)import ipywidgets as widgets

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

%matplotlib widget

%matplotlib inline

x = np.linspace(0, 50, 1000)

@widgets.interact(intercept=(-5, 5, 1.), slope=(0, 1, .05))

def update(intercept=0.0, slope=0.5):

plt.scatter(df["total_bill"], df["tip"])

plt.plot(x, intercept + slope * x, color="red")

plt.xlim((0, 50))

plt.ylim((0, 10))

plt.xlabel("total_bill", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("tip", fontsize=12)

This is kind of tedious to do this by hand… it would be nice to come up with an automated way of doing this. Moreover:

total_bill column to predict the tip, while we know about many other thingsdf.head()| total_bill | tip | sex | smoker | day | time | size | tip_percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 | 0.059447 |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 | 0.160542 |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 3 | 0.166587 |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | Male | No | Sun | Dinner | 2 | 0.139780 |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | Female | No | Sun | Dinner | 4 | 0.146808 |

We can’t perform computations (products and sums) with columns containing categorical variables. So, we can’t use them like this to predict the tip. We need to convert them to numbers somehow.

The most classical approach for this is one-hot encoding (or “create dummies” or “binarize”) of the categorical variables, which can be easily achieved with pandas.get_dummies

Why one-hot ? See wikipedia for a plausible explanation

df_one_hot = pd.get_dummies(df, prefix_sep='#')

df_one_hot.head(5)| total_bill | tip | size | tip_percentage | sex#Female | sex#Male | smoker#No | smoker#Yes | day#Fri | day#Sat | day#Sun | day#Thur | time#Dinner | time#Lunch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | 2 | 0.059447 | True | False | True | False | False | False | True | False | True | False |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | 3 | 0.160542 | False | True | True | False | False | False | True | False | True | False |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | 3 | 0.166587 | False | True | True | False | False | False | True | False | True | False |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | 2 | 0.139780 | False | True | True | False | False | False | True | False | True | False |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | 4 | 0.146808 | True | False | True | False | False | False | True | False | True | False |

Only the categorical columns have been one-hot encoded. For instance, the "day" column is replaced by 4 columns named "day#Thur", "day#Fri", "day#Sat", "day#Sun", since "day" has 4 modalities (see next line).

df['day'].unique()['Sun', 'Sat', 'Thur', 'Fri']

Categories (4, object): ['Fri', 'Sat', 'Sun', 'Thur']df_one_hot.dtypestotal_bill float64

tip float64

size int64

tip_percentage float64

sex#Female bool

sex#Male bool

smoker#No bool

smoker#Yes bool

day#Fri bool

day#Sat bool

day#Sun bool

day#Thur bool

time#Dinner bool

time#Lunch bool

dtype: objectSums over dummies for sex, smoker, day, time and size are all equal to one (by constrution of the one-hot encoded vectors).

day_cols = [col for col in df_one_hot.columns if col.startswith("day")]

df_one_hot[day_cols].head()

df_one_hot[day_cols].sum(axis=1)0 1

1 1

2 1

3 1

4 1

..

239 1

240 1

241 1

242 1

243 1

Length: 244, dtype: int64all(df_one_hot[day_cols].sum(axis=1) == 1)TrueThe most standard solution is to remove a modality (i.e. remove a one-hot encoding vector). Simply achieved by specifying drop_first=True in the get_dummies function.

df["day"].unique()['Sun', 'Sat', 'Thur', 'Fri']

Categories (4, object): ['Fri', 'Sat', 'Sun', 'Thur']pd.get_dummies(df, prefix_sep='#', drop_first=True).head()| total_bill | tip | size | tip_percentage | sex#Male | smoker#Yes | day#Sat | day#Sun | day#Thur | time#Lunch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.99 | 1.01 | 2 | 0.059447 | False | False | False | True | False | False |

| 1 | 10.34 | 1.66 | 3 | 0.160542 | True | False | False | True | False | False |

| 2 | 21.01 | 3.50 | 3 | 0.166587 | True | False | False | True | False | False |

| 3 | 23.68 | 3.31 | 2 | 0.139780 | True | False | False | True | False | False |

| 4 | 24.59 | 3.61 | 4 | 0.146808 | False | False | False | True | False | False |

Now, if a categorical feature has \(K\) modalities/levels, we use only \(K-1\) dummies. For instance, there is no more sex#Female binary column.

Question. So, a linear regression won’t fit a weight for sex#Female. But, where do the model weights of the dropped binary columns go ?

Answer. They just “go” to the intercept: interpretation of the population bias depends on the “dropped” one-hot encodings.

So, we actually fit:

\[ \begin{array}{rl} \texttt{tip} \approx b & + w_1 \times \texttt{total\_bill} + w_2 \times \texttt{size} \\ & + w_3 \times \texttt{sex\#Male} + w_4 \times \texttt{smoker\#Yes} \\ & + w_5 \times \texttt{day\#Sat} + w_6 \times \texttt{day\#Sun} + w_7 \times \texttt{day\#Thur} \\ & + w_8 \times \texttt{time\#Lunch} \end{array} \]